Beginning Years:

Beginning Years:

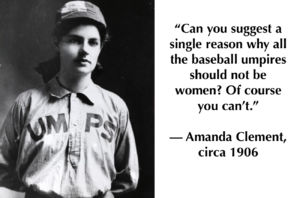

Amanda Clement was born in 1888 in Hudson, South Dakota. Amanda was familiar with strong women her entire life. Her dad died when she was seven, so Amanda watched as her mother stepped up to the plate and took on the challenge of raising two children alone. It was a social crime to parent kids without a man in the house, let alone a young boy. However, Amanda watched as her mother ignored the critics and raised her brother and herself all alone.

Amanda grew up playing sports with her brother, Hank, but her favorite was baseball. There was a field across from Clement’s house, so all the neighborhood kids would gather to play with Amanda and Hank. Back then, society didn’t consider it socially appropriate for a girl to play with boys, so Amanda was often forced to be the umpire. Only when a boy was missing could Amanda sub-in.

In 1904, when Amanda was 16, Hank was signed with a semi-professional team and traveled all over the midwest for games. Amanda and her mom decided to travel to a few of these games to support Hank. It was during a game in Iowa that Amanda was called to save the day.

The two teams played a warm-up game, and the umpire could not attend. During this time, only one umpire in a game was positioned behind the pitcher’s mound, so there was no backup umpire on hand. Hank nominated Amanda to fill the role, and the teams agreed. The next day, the umpire was still nowhere to be seen, and the game was about to start. The teams were so impressed with Amanda’s work from the day before that they hired her on the spot to ump the game. Thus was born the legend of Amanda Clement– the first women umpire.

College Years:

After the first game, Amanda regularly umpired for six consecutive years. She only umpired in the summer, as she attended school for the rest of the year. After finishing high school, Amanda went to Yankton college for two years, then the University of Nebraska-Lincoln for two years. She was able to pay her way through college with the money she made while umpiring. Amanda umpired about 50 games each summer, and for each game, she charged $15-$25; the modern-day equivalent of that is around $600-$800 per game.

After the first game, Amanda regularly umpired for six consecutive years. She only umpired in the summer, as she attended school for the rest of the year. After finishing high school, Amanda went to Yankton college for two years, then the University of Nebraska-Lincoln for two years. She was able to pay her way through college with the money she made while umpiring. Amanda umpired about 50 games each summer, and for each game, she charged $15-$25; the modern-day equivalent of that is around $600-$800 per game.

Amanda became a sensation. Everyone wanted to see her in action, and every team wanted her on their field. For any game of importance, she was the first person called. She received so many requests that Amanda got to pick which games she wanted to ump purely by where she wanted to travel. She went all over the midwest for games and branched out to states such as Colorado, New Mexico, Louisiana, and Massachusetts.

Newspapers from all over the United States reported on Amanda. Many rumors were made about her as she became more famous. One of the most prominent rumors was published in a Boston newspaper and stated that she had received over 60 marriage proposals from baseball players in her league. She responded by saying, “I am wedded to baseball” and that people should not listen to gossip. Though the marriage proposals were made up, Amanda was a heartthrob for the men of the baseball community. One man, Will Chamberlain, even wrote poetry about her and published it in the local newspaper.

As her popularity grew, promoters did something they had never done before: they listed the umpire’s name on all promotional material for the games instead of the players. They did this because Amanda had a much bigger draw than the players.

Once in Oakes, ND, Amanda, and a man were hired to Ump a series of games together. However, the fans collected money to pay for the man’s fees and transportation back home so they could watch Amanda officiate all the games on her own.

Her appeal didn’t stop at the minor leagues. Ban Johnson, president of the American League, and Harry Pulliam, president of the National League, tried to persuade her to become a major league umpire. However, she turned them down because she wanted to continue her education.

At the time, she was one of the most famous women in America. In fact, during his visit to South Dakota in 1910, President Roosevelt was introduced to Amanda. He said that he had read a great deal about her, and she responded by saying that she could say the same about him. They spent the evening together and became friends for a while after that.

Amanda’s sporting skills didn’t stop at baseball. While at Yankton College, she competed in baseball, basketball, track, gymnastics, and tennis. For a couple of months, she filled in on the boy’s baseball team, playing first base. She was captain of the basketball team and held the school records for running broad jump and standing high jump. She also was the tennis champion for Iowa and South Dakota. While there, she set a national record for a female throwing a baseball; she threw it 279 ft– 50 ft short from the length of a football field. Historians also speculate that she held some unofficial world records in shot put, sprinting, hurdling, and baseball.

Amanda was an excellent coach and taught sports for most of her life. While in college, she coached various sports, from basketball to volleyball to wrestling. While at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Amanda taught ballet to the University of Wyoming football team. She also had a knack for refereeing. While in Yankton, she refereed for high school basketball and intramural games. On top of being the first female umpire, Amanda was also the first female referee.

After College Years:

After college Amanda stopped umpiring professionally; however, she umpired intermittently until her forties. She spent her first years out of college teaching physical education at various high schools and colleges. In 1911, she moved to LaCrosse, Wisconsin, to manage the local YWCA. While in Lacrosse, she pulled a drowning man from a river and performed CPR to save his life. In 1915, she moved to Keokuk, Iowa, to serve as the physical education director of the YWCA there.

After college Amanda stopped umpiring professionally; however, she umpired intermittently until her forties. She spent her first years out of college teaching physical education at various high schools and colleges. In 1911, she moved to LaCrosse, Wisconsin, to manage the local YWCA. While in Lacrosse, she pulled a drowning man from a river and performed CPR to save his life. In 1915, she moved to Keokuk, Iowa, to serve as the physical education director of the YWCA there.

In 1930, Amanda moved to Sioux Falls to care for her sick mother. While there, she became a welfare/social worker. Amanda also became involved in the Sioux Falls YWCA as soon as it opened. While she didn’t want to serve on the board, she played a crucial role in establishing a physical education program in the organization. After her mother died in 1934, Amanda joined the Health Education Committee for the YWCA.

She attended many YWCA conferences and represented the Sioux Falls chapter. She advocated strongly for funding for sports and teams. During her time with the YWCA, she served as a volleyball coach, baseball coach, and basketball coach, and she created a “game class” that taught women the rules and techniques of various sports.

In 1932, Amanda became one of the first women justices of South Dakota and officiated her cousin’s wedding. As a justice, she often reversed the common phrase and asked brides to “kiss their groom.”

Amanda was awarded for her efforts in baseball. As of today, she is a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY, the International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame in East Meadow, NY, the Women’s Sports Foundation in San Francisco, CA, the Yankton College Alumni Hall of Fame in Yankton, SD, and she has a profile in Sports Illustrated Magazine. Amanda was also the second woman inducted into the South Dakota Sports Hall of Fame in 1982. Additionally, she has a children’s book written about her titled umpire in a Skirt.

Amanda never had a husband or kids but loved her brother’s family. She taught her nieces and nephews how to play baseball. Her nephew said that while playing with her, they used to run inside “for water” and put sponges in their gloves because she threw so hard.

Amanda died in 1971 at the age of 83. Even after she stopped umpiring, she never lost her love of the sport. She went to many local games and always cheered for her favorite team, the Minnesota Twins.

Amanda died in 1971 at the age of 83. Even after she stopped umpiring, she never lost her love of the sport. She went to many local games and always cheered for her favorite team, the Minnesota Twins.

At EmBe, we hope to uphold Amanda’s ambition and grit in everything we pursue. For the past 100 years, passionate women like Amanda have helped to make our organization strong. In our next 100 years, we hope to inspire all our members to relentlessly pursue their passions so we can be as revolutionary as those who came before us.